- Joined

- Jul 27, 2009

- Messages

- 4,102

We tend to think of diamond as a totally transparent material but that is not always the case. Sometimes diamonds are hazy and often described as looking “milky”. Diamonds can appear milky for a number of reasons. Most often the cause is related to the presence of clarity characteristics such as microscopic inclusions, but can also be the result of defects at the atomic level in the carbon lattice. Strong fluorescence, particularly in combination with light scattering inclusions, can also cause a loss of transparency resulting in the diamond having a hazy or milky appearance.

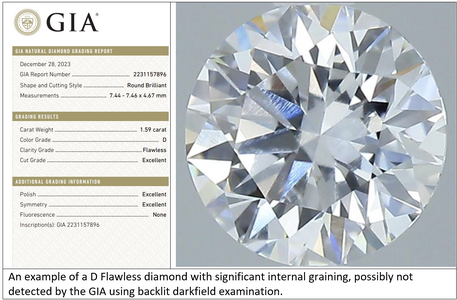

It should be noted that transparency is not currently graded or measured on a laboratory report, arguably a failing of the laboratory community given how common transparency issues are and how much they can affect the appearance and performance of faceted diamonds. But there are sometimes clues to a transparency issue if you understand the nuanced way reports communicate certain information. In laboratory grown diamonds, atomic level transparency issues are more common, as we will discuss below in a separate section. Otherwise, this article is generally aimed at natural, mined diamonds.

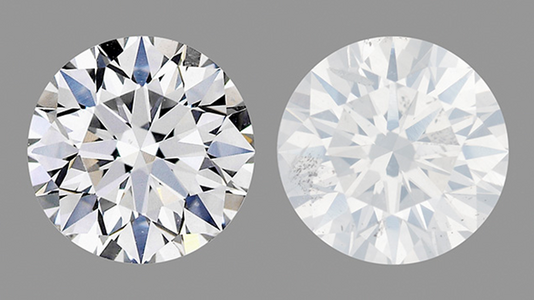

Transparency deficits can be very subtle and require a trained eye to assess accurately. Sometimes online images will reveal them, though they may not be obvious - particularly images taken in diffuse lighting. Directional lighting (such as spot lighting) can show the effect more prominently. But being able to compare to a diamond with full transparency is often required.

Milkiness in diamond on right is subtle in diffuse lighting above

Clarity Features as Cause of Milkiness

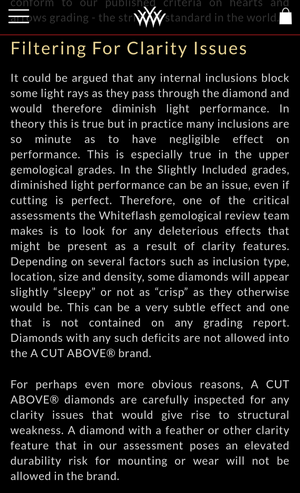

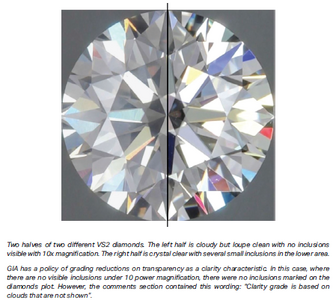

Inclusions can cause light to be scattered and prevent light rays from fully propagating through a diamond. This can result in a hazy, cloudy or milky appearance depending on severity. Light scattering inclusions such as twinning wisps, graining, and clouds can interfere with light rays as they are internally reflected within the diamond. As they exit the crown on their way to our eye those rays are degraded to a point where they no longer have the sparkle or fire we expect from a fully transparent diamond. Depending on the extent of the interference, the diamond may have only very slightly diminished transparency that is not obvious to the untrained observer. But if the inclusions are extensive and dense enough or the distortions in the carbon lattice severe enough, the degradation can be obvious – a dull diamond that has no life. It’s a diamond that looks perpetually like it needs professional cleaning.

In natural diamonds the chance of this being the case in the high clarity grades is extremely low. The problem usually exists in the Si and below range. It is also possible in the VS range, particularly VS2 that might be on the border of Si1.

Fluorescence can Cause a Diamond to be Milky

About 30% of natural diamonds have a property known as photoluminescence – most commonly called fluorescence. The strength of the effect varies from none or very faint to strong and very strong. It is known that some strongly fluorescent diamonds appear milky. A 2021 GIA study on the subject found that most of the fluorescent diamonds that show diminished transparency also contain light scattering inclusions and that fluorescence alone does not cause milkiness. Therefore, if you are considering a fluorescent diamond it is wise to avoid those stones with graining, twinning wisps and cloud inclusions.

The same GIA study also revealed for the first time that strong fluorescence can cause diminished contrast, a component necessary for optimal scintillation. It is possible that this factor may contribute to the perception of the diamond appearing a little flat. This, in combination with light scattering inclusions in the presence of strong fluorescence may be a more complete explanation of why strongly fluorescent diamonds sometimes appear milky.

Atomic-level Defects can cause of Milkiness

Diamond is composed of pure carbon atoms bonded to one another in a regular lattice structure. Diamonds are formed as carbon atoms are laid down layer by layer upon this lattice.

But during formation diamonds can undergo forces that alter the regular pattern of their carbon lattice. In addition to trace elements being introduced such as nitrogen, hydrogen, boron and nickel, other defects can occur such as atomic vacancies in the lattice. Strain can also occur causing the lattice to be deformed. Defects in the lattice can have many different effects including causing the diamond to have body color, fluorescence, and also to have diminished transparency.

Laboratory Grown Diamonds - Strain and Striation can cause Milkiness

As noted above, atomic level defects can have impacts on transparency. This is relatively common in laboratory grown diamonds, particularly those grown by the CVD method. Whereas HPHT grown diamonds are rigidly constrained during growth by enormous pressure from all sides, CVD grown diamonds are not. This can lead to deformation of the carbon lattice in the form of crystal strain. Strain in diamond can best be seen when viewed through polarizing filters, but if severe enough can also affect its visual appearance causing a faceted diamond to have a roiled look. This can cause the virtual facets to look blurry and for the stone to take on a slight haziness. A diamond with this problem will never achieve optimal light performance, no matter how precisely cut. Unfortunately, there is nothing on a laboratory report to draw attention to a problem of this nature.

The CVD growth method allows an operator the opportunity to stop and re-start the process, sometimes to correct problems that can be observed through a view window on the CVD machine. Starting and stopping can present its own set of problems however, in the form of striations in the carbon lattice. This is a type of graining due to fluctuations in the growth environment and if severe enough can make the diamond look milky. HPHT growth is done in a single uninterrupted run and normally produces diamonds with no appreciable striation, little strain, and generally no transparency issues.

BGM – Brown, Green, Milky

Milky diamonds have a stigma in the market which derives from the diminished fire and brilliance they possess, even when precision cut. Two other characteristics are likewise stigmatized in the market for different reasons. Diamonds in the “normal” color range (D-Z) are graded on the basis of the degree to which they have body color in the brown and yellow hues. Brown in particular is considered by many to be less desirable than yellow. And rough diamonds with a greenish skin from natural irradiation stains sometimes show a green hue when faceted. These diamonds are highly associated with origins in Zimbabwe (Marange diamond field), and with the political infighting and human rights abuses which led to a ban on trading diamonds from the country.

To underscore the stigma associated with these three particular characteristics, some diamond manufacturers have developed a designation on their trade listings as “No BGM”, meant to assure their clients that the diamond in the listing is free of these issues.

Fancy White Diamonds – the Ultimate Milky Diamond

Milky diamonds are generally not desirable. That is, unless they are so milky that they cross over into the fancy color diamond realm. The ultimate milky diamonds are those that appear white (not to be confused with colorless diamonds that are often referred to as white). The nano-level inclusions and atomic level “dislocation loops” that typically cause this level of milkiness can make the diamond almost opaque. The best of these rare diamonds are sometimes described as having an opalescent appearance.

Fancy white diamond on right above

Conclusion

Diamonds are not always fully transparent. There are a number of causes for diminished transparency including light scattering clarity characteristics such as twinning wisps, clouds and graining as well as defects in the carbon lattice such as strain. Strong fluorescence can also cause diminished transparency, usually in the presence of light scattering inclusions. Depending on the severity of the issue a diamond with diminished transparency will look hazy or milky, or just lack the crisp scintillation, fire and brilliance we expect from a gem diamond.

Because no major diamond laboratory yet measures or grades transparency, it is up to the consumer to understand how to detect an appreciable transparency problem. This can require a trained eye to assess accurately. Knowing how to interpret some of the nuances of a laboratory report can be helpful as there are sometimes clues to be gleaned from them.

Transparency issues in natural diamonds are generally caused by clarity characteristics such as graining, twinning wisps and clouds and are more prevalent in the lower clarity grades. Laboratory grown diamonds on the other hand are more likely to have transparency issues due to atomic level defects such as strain and striation, even in the highest clarity grades.

______

What are your thoughts on the importance of fully transparent diamonds?

It should be noted that transparency is not currently graded or measured on a laboratory report, arguably a failing of the laboratory community given how common transparency issues are and how much they can affect the appearance and performance of faceted diamonds. But there are sometimes clues to a transparency issue if you understand the nuanced way reports communicate certain information. In laboratory grown diamonds, atomic level transparency issues are more common, as we will discuss below in a separate section. Otherwise, this article is generally aimed at natural, mined diamonds.

Transparency deficits can be very subtle and require a trained eye to assess accurately. Sometimes online images will reveal them, though they may not be obvious - particularly images taken in diffuse lighting. Directional lighting (such as spot lighting) can show the effect more prominently. But being able to compare to a diamond with full transparency is often required.

Milkiness in diamond on right is subtle in diffuse lighting above

Milkiness is more pronounced in directional lightingClarity Features as Cause of Milkiness

Inclusions can cause light to be scattered and prevent light rays from fully propagating through a diamond. This can result in a hazy, cloudy or milky appearance depending on severity. Light scattering inclusions such as twinning wisps, graining, and clouds can interfere with light rays as they are internally reflected within the diamond. As they exit the crown on their way to our eye those rays are degraded to a point where they no longer have the sparkle or fire we expect from a fully transparent diamond. Depending on the extent of the interference, the diamond may have only very slightly diminished transparency that is not obvious to the untrained observer. But if the inclusions are extensive and dense enough or the distortions in the carbon lattice severe enough, the degradation can be obvious – a dull diamond that has no life. It’s a diamond that looks perpetually like it needs professional cleaning.

In natural diamonds the chance of this being the case in the high clarity grades is extremely low. The problem usually exists in the Si and below range. It is also possible in the VS range, particularly VS2 that might be on the border of Si1.

Fluorescence can Cause a Diamond to be Milky

About 30% of natural diamonds have a property known as photoluminescence – most commonly called fluorescence. The strength of the effect varies from none or very faint to strong and very strong. It is known that some strongly fluorescent diamonds appear milky. A 2021 GIA study on the subject found that most of the fluorescent diamonds that show diminished transparency also contain light scattering inclusions and that fluorescence alone does not cause milkiness. Therefore, if you are considering a fluorescent diamond it is wise to avoid those stones with graining, twinning wisps and cloud inclusions.

The same GIA study also revealed for the first time that strong fluorescence can cause diminished contrast, a component necessary for optimal scintillation. It is possible that this factor may contribute to the perception of the diamond appearing a little flat. This, in combination with light scattering inclusions in the presence of strong fluorescence may be a more complete explanation of why strongly fluorescent diamonds sometimes appear milky.

Atomic-level Defects can cause of Milkiness

Diamond is composed of pure carbon atoms bonded to one another in a regular lattice structure. Diamonds are formed as carbon atoms are laid down layer by layer upon this lattice.

But during formation diamonds can undergo forces that alter the regular pattern of their carbon lattice. In addition to trace elements being introduced such as nitrogen, hydrogen, boron and nickel, other defects can occur such as atomic vacancies in the lattice. Strain can also occur causing the lattice to be deformed. Defects in the lattice can have many different effects including causing the diamond to have body color, fluorescence, and also to have diminished transparency.

Laboratory Grown Diamonds - Strain and Striation can cause Milkiness

As noted above, atomic level defects can have impacts on transparency. This is relatively common in laboratory grown diamonds, particularly those grown by the CVD method. Whereas HPHT grown diamonds are rigidly constrained during growth by enormous pressure from all sides, CVD grown diamonds are not. This can lead to deformation of the carbon lattice in the form of crystal strain. Strain in diamond can best be seen when viewed through polarizing filters, but if severe enough can also affect its visual appearance causing a faceted diamond to have a roiled look. This can cause the virtual facets to look blurry and for the stone to take on a slight haziness. A diamond with this problem will never achieve optimal light performance, no matter how precisely cut. Unfortunately, there is nothing on a laboratory report to draw attention to a problem of this nature.

The CVD growth method allows an operator the opportunity to stop and re-start the process, sometimes to correct problems that can be observed through a view window on the CVD machine. Starting and stopping can present its own set of problems however, in the form of striations in the carbon lattice. This is a type of graining due to fluctuations in the growth environment and if severe enough can make the diamond look milky. HPHT growth is done in a single uninterrupted run and normally produces diamonds with no appreciable striation, little strain, and generally no transparency issues.

BGM – Brown, Green, Milky

Milky diamonds have a stigma in the market which derives from the diminished fire and brilliance they possess, even when precision cut. Two other characteristics are likewise stigmatized in the market for different reasons. Diamonds in the “normal” color range (D-Z) are graded on the basis of the degree to which they have body color in the brown and yellow hues. Brown in particular is considered by many to be less desirable than yellow. And rough diamonds with a greenish skin from natural irradiation stains sometimes show a green hue when faceted. These diamonds are highly associated with origins in Zimbabwe (Marange diamond field), and with the political infighting and human rights abuses which led to a ban on trading diamonds from the country.

To underscore the stigma associated with these three particular characteristics, some diamond manufacturers have developed a designation on their trade listings as “No BGM”, meant to assure their clients that the diamond in the listing is free of these issues.

Fancy White Diamonds – the Ultimate Milky Diamond

Milky diamonds are generally not desirable. That is, unless they are so milky that they cross over into the fancy color diamond realm. The ultimate milky diamonds are those that appear white (not to be confused with colorless diamonds that are often referred to as white). The nano-level inclusions and atomic level “dislocation loops” that typically cause this level of milkiness can make the diamond almost opaque. The best of these rare diamonds are sometimes described as having an opalescent appearance.

Fancy white diamond on right above

Conclusion

Diamonds are not always fully transparent. There are a number of causes for diminished transparency including light scattering clarity characteristics such as twinning wisps, clouds and graining as well as defects in the carbon lattice such as strain. Strong fluorescence can also cause diminished transparency, usually in the presence of light scattering inclusions. Depending on the severity of the issue a diamond with diminished transparency will look hazy or milky, or just lack the crisp scintillation, fire and brilliance we expect from a gem diamond.

Because no major diamond laboratory yet measures or grades transparency, it is up to the consumer to understand how to detect an appreciable transparency problem. This can require a trained eye to assess accurately. Knowing how to interpret some of the nuances of a laboratory report can be helpful as there are sometimes clues to be gleaned from them.

Transparency issues in natural diamonds are generally caused by clarity characteristics such as graining, twinning wisps and clouds and are more prevalent in the lower clarity grades. Laboratory grown diamonds on the other hand are more likely to have transparency issues due to atomic level defects such as strain and striation, even in the highest clarity grades.

______

What are your thoughts on the importance of fully transparent diamonds?

300x240.png)