Posted the other day in the August thread. I am adding it here where it belongs.

"

One shot per year? We really need to step up our game then

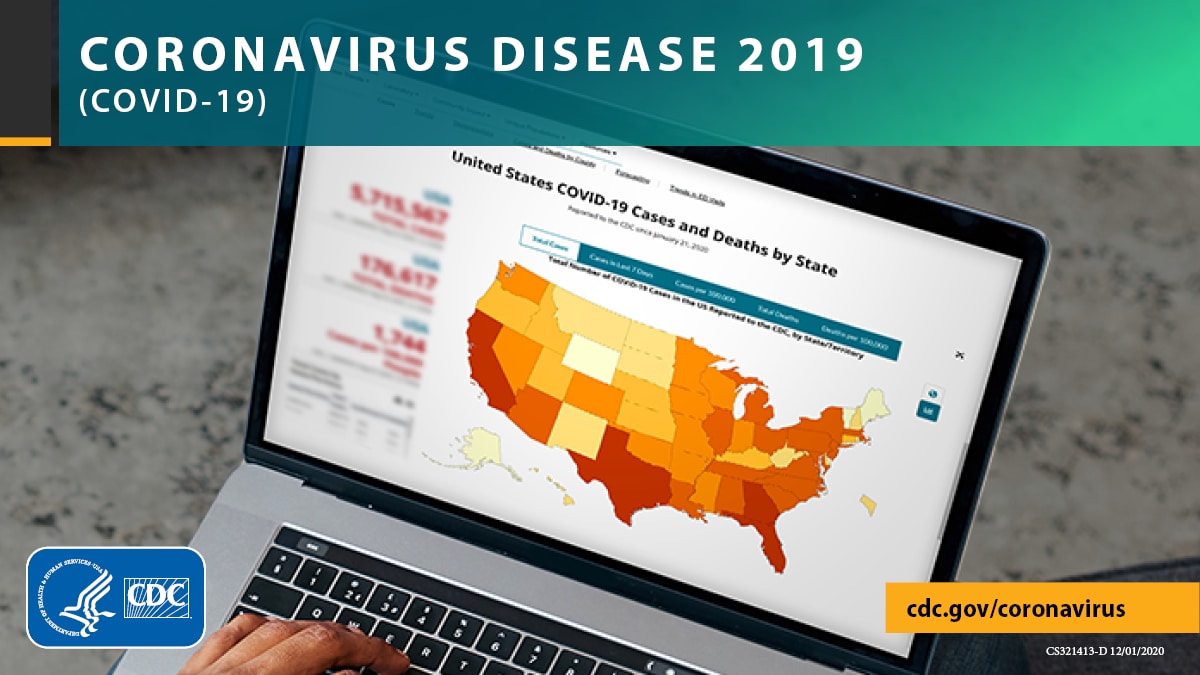

Yesterday, the White House announced a new plan: one COVID-19 shot per year. The idea is this will decrease public confusion and increase booster uptake by aligning with the flu vaccine campaign. Reading between the lines, I think this is also a political signal to shift out of the SARS-CoV-2 emergency phase.

Katelyn Jetelina

Sep 7

Will an annual shot plan work? Maybe. But there’s a lot that needs to align beforehand. And I certainly hope this doesn’t mean we are accepting our current state of affairs with vaccines.

Stars need to align

The annual COVID-19 plan largely follows our flu model: evaluate circulating strains and update the vaccine before the flu season. This model works for the flu for three main reasons:

SARS-CoV-2 is mutating 4 times faster than the flu. It’s not seasonal nor annual. It’s not mutating in a ladder like form. And we do not have global surveillance systems in place. We expect and hope that COVID-19 will eventually be like the flu but to assume that has already happened is premature. I also think it is a gamble, as the virus continues to surprise us. To pivot the public—again—is risky.

- Flu is clearly seasonal. The predictability of the flu allows us to time vaccine recommendations so that vaccine companies can manufacturer and distribute by winter. A 6-month flu season also means that we really only need our flu to cover the winter months. In other words, the vaccine can wane, particularly among older populations.

- Flu mutations have direction. As I have written before, the flu mutates in a ladder-like pattern. This allows us to “predict” the direction the flu may be mutating.

- Flu has been around for decades, which has allowed us to develop and refine global surveillance systems to identify emerging strains.

The fall bivalent vaccine is also our first attempt to apply the flu model to SARS-CoV-2. This is our pilot. And we really need to see how the pilot works in the “real world” before making sweeping declarations, like an annual shot. We need the data, the time, and the humility to tell. Let’s first get through winter.

Up our vaccine game

The annual COVID-19 booster plan also means the White House has one goal: prevent severe disease and death. And our first generation vaccines can do this well. In fact, the first generation vaccines saved an estimated 20 million lives across the globe in one year.

However, we can and should do better. This does not mean boosting our way out of the pandemic, but it means leveraging innovation and science to develop next generation vaccines that last longer and/or prevent infection/transmission. This would have immense, positive ripple effects. It would slow transmission. It would slow viral mutations. It would slow morbidity (long COVID-19). It could sunset the pandemic.

Next generation vaccines include:

These next generation vaccines are obtainable. We are well on our way, but this cannot be accomplished without investment from Congress. It costs an estimated $1 billion to develop and test a drug or vaccine from start to finish. And it takes risk, as not every vaccine makes it through clinical trials. Money will move mountains in science and research. But we need a push from the public, and a push from the administration. We need an Operation Warp Speed 2.0.

- Mucosal vaccines. Nasal and/or oral vaccines would provide more protection against infection and transmission (i.e., sterilizing immunity). Thirteen nasal vaccines are currently in development. These work very differently from our current vaccines, as they target “mucosal” immunity. Mucosal tissue is all over our body, including our nose and throats. In fact, it’s the largest component of our immune system and is one of the first defenses with the elements in the real world. By providing immunity there (instead of deep within our circulatory system) we can prevent infection in the first place. Clinical trial data is incredibly promising, especially when used as a booster (opposed to the primary series). This week, China approved the world’s first inhaled booster against COVID-19 called Convidecia Air.

- Pancoronavirus vaccines. The next best thing to sterilizing immunity would be a variant-proof vaccine that lasts longer. As I’ve written before, there are several in development, but the one winning the race is from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research using “nanoparticle vaccine technology.” The vaccine presents a protein that looks like a soccer ball with many different faces. Each face presents instructions for a different part or version of a virus. We can include faces on it not just for SARS-CoV-2, but for other coronaviruses, too.

- Flu and COVID-19 combo vaccines. At the very least we need one vaccine that contains both the flu and COVID-19 vaccine formula. Earlier this year, Novavax released data on the Phase 1/2 clinical trial of its COVID-Influenza Combination Vaccine. Animal data showed this vaccine worked well, and currently 642 people aged 50-70 years old are in the Phase 1/2 clinical trial. If all goes well, a combo vaccine may be available by 2023 flu season. We need more options in case this one doesn’t make it through clinical trials.

Bottom line

The White House plans to have only one booster per year. This plan may (or may not) be a good one, as the stars would need to align for it to be effective. Regardless, next generation vaccines need to be a part of this conversation, as they are a critical solution for better health. We just need to fight for it.

"

So what do you do when the doctor says no mRNA vaccines for you as they did to my DD who came down with pericarditis after her booster? No one has an answer for her; not even the CDC.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/CMOGXIEEMJOELPAMMHVIDH3TOY.jpg)

300x240.png)